Research

Principles for best practice PLD PDF

Discussion: Some Initial Principles for Hangarau Professional Learning Development Design

Full text from thesis copied below

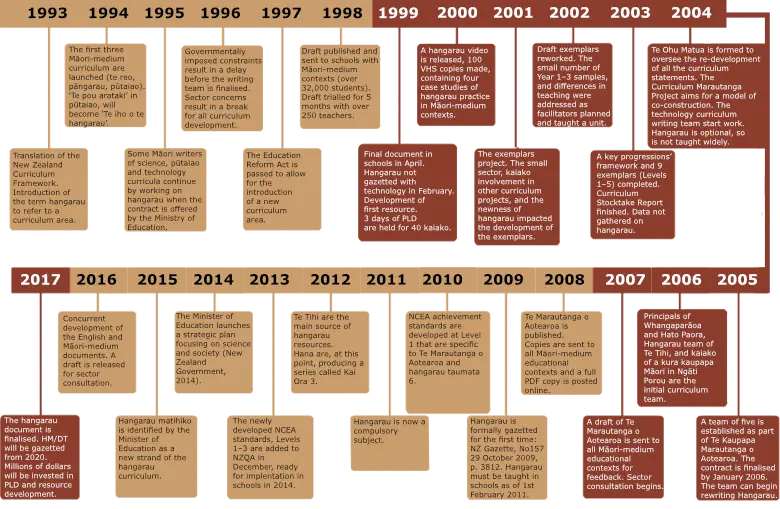

The principles outlined in this section were developed as a result of the important considerations identified in the literature. Particularly significant are the ideas that PLD should originate from an assets-based perspective and the call to address the scarcity of PLD developed specifically for the Māori-medium educational context (Marshall & McKenzie, 2011; Murphy et al., 2009). The analysis of the dataset and the resulting five notions outlined briefly above have been used in developing key principles to consider in the design of professional development for Māori-medium educators, specifically for the hangarau curriculum. The initial principles are as follows:

- PLD for small, limited-capacity communities should be bespoke, not one-size-fits-all. Much of the content currently being delivered to Māori-medium educators is not targeting Te Marautanga o Aotearoa.

- PLD needs to be strength-based, not deficit.

- PLD development should be delivered bilingually and designed using a te ao Māori lens (Murphy et al., 2009). If Māori medium is to claim the right to indigenise hangarau and other wāhanga ako, then it needs to be given the opportunity and the space to develop hangarau without its design being determined by the needs of the English-medium sector. The Māori-medium sector should determine their educational needs.

- Much of the literature identified principles that could be helpful if applied in specific ways. For example, longer periods of time, as they allow professionals time to engage with the new thinking. PLD needs to be differentiated, looking at appropriate delivery mechanisms such as andragogical approaches because the development is being delivered to adult learners (Knowles et al., 2020), allowing for the co-construction of development aims and buy-in and engagement from the teachers choosing to engage with this specific opportunity. There has been a move from a cascade approach, coaching and mentoring, to acknowledging the importance of a community of learners that may transcend the single school unit.

- There needs to be a balance of formal and informal opportunities, where teachers can discuss, model, observe, and be active in knowledge building, taking what they have learnt, practicing it with their students, and then returning to the group, sharing their feedback and feedforward: How did the innovation work in their classroom? What could they do to further innovate with their students?

- Current teachers require training, as do the next generation of teachers and teachers returning to the sector from overseas or a break in teaching; therefore, PLD must be ongoing.

- If we are to consider the imbalance between demand and supply—the small pool of mātanga and hangarau practitioners with the requisite skills and the corresponding requisite fluency in te reo Māori, we need to develop online materials that can be engaged with asynchronously or that kāhui ako [learning clusters or groups of schools generally geographically close to each other that can choose to work together in collaborative PLD opportunities] can engage with together. One of the caveats of working with asynchronous material as a busy professional is that it is challenging to make the time to engage. This can be mitigated if you work collectively through the asynchronous materials.

- Theories and rationale used to determine PLD models should be informed by systematic research in Māori-medium contexts. In 2012, the Ministry of Education contracted Pauline Waiti to consult with the sector and to develop a model that would be most efficient for Māori-medium contexts (Ministry of Education, 2003–2012). The outcome of the Hangarau Beacon Project was not available in the materials that the Ministry of Education had available about the marautanga hangarau; however, the author was told confidentially that this research had been cut short due to political reasons.